Ftrain, by Paul Ford

20 Most Recent

Erynn Petersen: Fixing Healthtech, One Bill at a Time

Can AI help heal our broken healthcare system? On this week’s podcast, Paul and Rich are joined in the studio by Erynn Petersen, a longtime technologist and the current CEO of Emme, a healthtech startup that works to lower medical costs for both providers and patients. First, she lays out some of the systemic problems that saddle Americans with huge bills (or lead them to avoid seeking care entirely). Then, she discusses how AI tools might revolutionize the industry—as well as the ways the technology could make an unequal system even worse.

Can AI help heal our broken healthcare system? On this week’s podcast, Paul and Rich are joined in the studio by Erynn Petersen, a longtime technologist and the current CEO of Emme, a healthtech startup that works to lower medical costs for both providers and patients. First, she lays out some of the systemic problems that saddle Americans with huge bills (or lead them to avoid seeking care entirely). Then, she discusses how AI tools might revolutionize the industry—as well as the ways the technology could make an unequal system even worse.

Unscroll Intro

It's bedtime. I'm very tired because I was cleaning today and I dropped a synthesizer on my head, leading to a lot of blood. But before I go, I'll share something totally broken.

About fifteen years ago I had this idea: Timelines on the World Wide Web! Hardly an original idea. But I got super into it. I thought I could somehow fix the world a little by making a great website that organized things chronologically. I had all kinds of pipe dreams along these lines. Laugh away at me, I deserve it. But also it's worth noting that we used to believe that making things on the Internet could make the world better. I even registered a URL, Unscroll.com.

As happens with my big ideas I kept aiming too high and never getting anything done. I kept approaching the problem from different angles, rather than taking small steps. For example, I decided that the only way I would finish my book about the web was to write a content management system that let you organize everything...in timelines. Now I had three problems!

The idea was you'd be scrolling timelines and you'd add little notes, and you'd transform the notes into a finished document with citations intact. Every paragraph would link to an event or fact. It would be amazing for students!

Unsurprisingly I managed to finish neither the book nor the CMS. People offered to help for both but I was way, way too inside the vortex. I built a lot of prototypes, and even presented them to large groups of people. I'll dig up videos at some point. I presented in Portland, Oregon, and I presented it at Lincoln Center for a creative software company conference, but mostly what I remember from that event was that, before I spoke, in the green room, I sat down and broke a plastic chair and fell with my legs in the air like a cartoon character, and it was, for a fat person, not the look for which I was going.

I did a ton of thinking about time. I learned a lot about how, for example, the Postgres database handles dates. I learned about different dating systems and calendars, and how various disciplines date things back to the beginning of the universe, and how the Library of Congress dates things. Chronology is hard. Time doesn't lend itself to becoming data, no matter what the stock market tells you. And parsing dates out of things is a nightmare. Wikipedia has a lot of chronological content—one page per year—but every year is formatted a tiny bit differently than all the others. I learned all of this and I was very happy to learn it. Nothing is more satisfying than learning about calendrical systems or the calculation of Easter. You feel how much people were stumbling in the dark, timewise. And it was all a further journey into procrastination.

A few months ago I grabbed all the old code and threw it into Claude. Goodness did it have some things to say about my programming. It's very flattering but you could tell it didn't mean it. Since then I've been poking at Unscroll, working on it “in production” on a server somewhere far from home—I don't want to give Claude domain over my local machine, you see.

Work is very busy and I'm suspicious of this project's ability to ruin my life so I try to have lots of little tasks for the bots over the weekend. Sometimes I work on it while on bike rides. Type, bike, type. It's in a very, very rough state. It's sub-alpha. But I thought it would be useful to resurrect it and talk about how things are changing. I'll noodle on it over time. Sort of like resurrecting Ftrain.

It took a while to just accept that we live in a sit-and-scroll world. The version in my head had multiple horizontal rows of spatialized data. But that's not how people read or learn now. We learn with one finger.

Things that used to be hard—parsing Wikipedia, extracting events from narrative content, aligning things by subject without a formal taxonomy (or with), and showing related stuff from the Internet Archive—are conceptually still very difficult but practically much easier. For example, not only is LLM-based coding good at writing custom parsers for Wikipedia, then QAing the results to improve the edge cases, but it was also instrumental in helping me download Kiwix, which gives me an offline Wikipedia, with images, so that I can “read” thousands of Wikipedia pages to look for relevant chronological content, then assemble that, then feed that into further queries for Archive.org and other platforms. This way I don't hammer Wikipedia. It also helped me convert the entire Wikiquote database, and found 90,000 quotes with dates.

What does it actually do? Well in the background it makes events, basically—little data blobs. Then it assembles them. Here's a timeline of Bach. If the system is not broken at the moment, you'll see that it includes many of the BWVs (his catalog) with Archive.org recordings, plus lots of related stuff from his life and parsed out of the big early biographies too. Learn about the Amiga Computer by reading old magazines! Learn the history of consciousness and AI or check out 200,000 years of human migration. Or just scroll. Some of it is very, very clunky. Lots just breaks.

It's not a good product yet and may never be. But it sure does keep me off social media. And it's something to talk about. I'd rather talk about work in particular than vibecoding in general.

I think some things to discuss are:

The basic architecture of things like this: Prototyping the CMS parts, creating user registration systems, and so forth.

How hard it is to get a system to be coherent when it has different ways of looking at data. LLMs excel at “view of the database” programming but when you go too far astray you need to think hard.

Refining and targeting a data model, and what that means for skills.

What's cheap to LLM, what's expensive.

Filtering for accuracy.

What an LLM should be allowed to reformat/rewrite, how it should rewrite, and how to document that and alert the user.

Automating the collection of research and source materials from large public corpora with humanist intent.

Getting access to tools that were previously pretty hard to pull off, like embeddings and vector search across events.

What “product” means in this context.

How to make it accessible—it's not right now.

What it means when platforms can be little hobbies.

And so forth. I'm noting this because I feel obligated to narrate the moment, especially since Simon Willison is putting in so much work, I should talk about this stuff too if it's helpful. Also I want to talk about the interaction between LLMs and content and computers—there's a lot to think through around pipelines that involve this new technology and how to be credible and transparent.

I'll open source it eventually if anyone cares and the data is all public/commons-ey stuff. I don't want to own time. I just want to experience it.

Dear God

Heading to work and a woman gets on the train, the middle of the car. She seems to be only in dirty underwear and holding bags. Just extremely unwell—screaming, stomping, swearing, repeating things, flopping around. Inchoate stuff. Really sad in there, all cylinders firing. Hard to hear clearly at all. People start moving towards the ends of the train, near me, to switch cars at the next station. But then a guy with a gentle voice tries to calm her down. “Gotta take a breath,” that sort of thing. She can't process it. She's not violent to anyone, or attacking anyone, but her body is actually flailing in space. And now she seems to be about to take a shit? Like she's yelling about it? That's what it sounds like. I'm getting it through my headphones. Very hard to know what's happening. The way people are moving away indicates something bad and biological is going down. I've seen things. Now everyone is lined up by the door, to switch cars as soon as the next stop. She seems to be screaming about something with her bowels, like she's sort of both psychically and physically constipated. Absolute agony. “I gotta shit!” Maybe? So confusing. Then suddenly she screams, clear as can be, “I just want to die, I just want to commit suicide.” A beat. And the gentle man's voice says: “Now that's crazy talk.”

Squeezed Faces

A strange thing my brain does now: I get onto a train or walk down a street and I'm slightly perplexed that I don't know the people I'm seeing. They all look familiar. But then I realize: I've lived here 30 years, I take this route every day, and so that makes sense: Everyone, statistically, remains a stranger. But nonetheless I keep looking around. Who's that? Do I know them? Did I work for them? Or did they work for me?

In the immediate neighborhood of my house, or right outside the office, I might see a familiar face—but each location is a tiny puddle of light in the great shadowy map. It's a world full of strangers.

For a while I thought my brain was slowing down but I think instead it's just compressing things, putting them together in its strange brain way. You meet thousands of people over years. It's just normal and accretive when you live and work in a giant city. They come through your house for parties or through your office for work events. And you multiply that by years. All those faces and names get stored away. Eventually your brain fills up and needs to compress the database. And as a result individual examples collapse into archetypes: Pudgy dads in sweaters, middle-aged moms in cool overalls, sons and daughters in their pajama-style clothing. Then I look around in the city, and I see those archetypes everywhere, and they feel so familiar. I don't know who anyone is, but they all look like people I've met.

I wonder if this is normal. My guess is it is. It's probably why some dads—the non-angry dads, with normal regrets—end up getting quite sweet starting in their 50s, glad to talk to everyone, asking a kid about his Pokémon or listening to someone explain what it's like to work at the bank, or letting someone tell them about pilates. It's not because we're becoming more gentle, it's just that we're no longer as good at seeing the edges of people and a lot of the time we don't have any idea who's talking to us. We stop seeing what's different about the individual and instead start seeing what unifies them. And we like it.

Another Disaster

What a mess. It had been two weeks. I'd practiced but not steadily. Hands like spiral-cut hams. Fingers like hard-boiled eggs. Not playing, flapping. I forgot one of my lesson books. I wanted to cancel so bad. I wanted a good excuse, a terrible illness, a broken limb, plague. I have bad excuses. I keep having that strong-pour evening cocktail. Just one but still. I've stopped getting downstairs to say goodbye to my son as he goes off to school, so I don't have the 20 minutes of morning quiet. I went to do a blood draw in the morning, right before the lesson. I didn't have my coffee as a result, since I'd been fasting. So I was extra groggy. These all went through my head and I mumbled them. But the truth is I just didn't practice very well. I half-practiced and I felt like a dipshit. I had this tiny little fantasy it would all come together. But it didn't. There's only one way to fix it. I hate piano. I chose this.

Product Is More Than Prompts

People are constantly talking about how AI is transforming engineers’ work, but where does that leave the product manager? On this week’s podcast, Paul (who has hired many PMs) and Rich (who is also a PM himself) tilt the AI-and-code lens away from the engineers and onto the role they describe as the diplomat of software creation, liaising between business, design, and engineering needs. Should PMs feel threatened by LLMs, or empowered by them? How can they use these tools to add value to the org and their role within it?

People are constantly talking about how AI is transforming engineers’ work, but where does that leave the product manager? On this week’s podcast, Paul (who has hired many PMs) and Rich (who is also a PM himself) tilt the AI-and-code lens away from the engineers and onto the role they describe as the diplomat of software creation, liaising between business, design, and engineering needs. Should PMs feel threatened by LLMs, or empowered by them? How can they use these tools to add value to the org and their role within it?

Pascal’s Fail State

This prominent MAGA-adjacent cartoonist died recently and did a Pascal’s wager-style deathbed conversion from atheism to Christianity, which, sure, whatever, humans. (Prayers are distributed through a supernatural network protocol they call pleamail—unfortunately most go to spam.) But his was flagged VIP, I'm sure it got through—so I keep thinking of him dying and ending up in all kinds of various other non-Christian hells, and the devils are poking him with sticks and going: “Dude, you almost had it, you almost had the peace of total nonexistence. But then you sent us that conversion notice. Now me and the guys have to torture you forever. Allahu akbar/Om namo bhagavate vasudevaya.” And they’re all Dogbert.

Morning and Night

<i>Robins m’aime</i>

New York is buried under snow, the State of the Union is going on, I'm rattling with anxiety as emails pile up, and I need to practice piano.

I have, in the manner of the true dilettante, secreted keyboards about the house. I'm a huge nerd, I needed something to fill my brain, I did well in life, and so I have a genuinely glorious little studio, bundles of wires running thick as a large man's wrist, modules, keyboards. It requires constant configuration. I would trade the kingdom of heaven for that one perfect knob. Anyway. One day I will have a small hut in the woods with no Internet and a decrepit piano that I will watch YouTube videos to learn to tune, and spend two years really learning, truly intuiting, probably with psilocybin assistance, the deep and Pythagorean complexities inherent in the equal temperament tones of the C major scale, or as I prefer to call them, the big naturals.

So I turn from this computer to the heavy, glorified MIDI controller to my right, made by a really kind of wonderful French brand, and I go through my pieces.

A miracle this week—I played the first part of the first Bach Minuet for the five or six thousandth time, and my left hand was in steady communication with my right hand. And there I was in the middle. Guys! I said. I didn't know you'd ever met! They said nothing.

All progress feels like a miracle. The State of the Union is probably still going as I type this. But over here a tiny, infinitesimal bit of progress. Something getting better. Don't knock it.

Across the hall my wife prints whistles on a 3D printer. Different music.

My left hand is normally a lumbering, grumbling donkey clambering up a mountain path, dragged along by my bouncy, energetic right hand. Piano teachers call this the Onan conundrum. But tonight they were dancing together like witches around a fire. Eventually I ran out of measures and reverted to failure mode, but now I know how it should feel. My teacher likes to say that your hands are in a band, which—I've never been in a band, he's been in so many, it's a normal thing for him. I wish I understood.

I bought, in Philadelphia, at this huge bookstore with a cat that I can't remember the name of (store/cat), the Norton Anthology of Western Music or whatever, in two volumes, and I gotta tell you, now that I can read music (both clefs!) the idea of picking up some song from 1250 and just plinking it out, it's a delight. So tonight I learned “Robins m'aime,” a French song by the 13th-century composer Adam de la Halle. I need to work on my sight reading and why not be medieval? But also it's magical. Over time language becomes inscrutable. Accents fade. Countries come and go. But a dude writes a song for Marion to sing about her guy Robin, and I can just pick that up, read the notes, and it's back in the world, the same song.

Robin bought me a surcote grand

Of scarlet cloth fine and bonny

Gown and kirtle gay as any.

I will have it!

A song about a man treating you right. Like a million such today. Do I despair that consciousness doesn't evolve? Yes! See the psilocybin meditations on tone. Éliane Radigue just passed, and my god. Imagine hearing Trilogie de Mort in your head, having that there, in your brain, then making it real. What a freaking consciousness that was. If you don't know it book three hours of your life, because you are about to learn what communicating with aliens will be like. I'm going to listen to it right now.

Like I said: Imagine having that in your head, but not yet recording it. I really do love that moment when an idea is just your own. You know you have to share it. It might die upon release. But the joy of it, of just containing something that feels new, before it must become actualized. The little inner motions of thought.

Anyway. You can, if you work at it for a few years, sit down and play haltingly a medieval song, just with your own eyes and fingers. No one can stop you. You can wear headphones and sing the song of Marion in 1250, and to hell with that interloping knight, because Robin is the man for me, he got me a kirtle.

And my hands are friends now. The world can be out there, pissing all over itself, and you can log off. You don't even have to put a picture on the top of the blog post. Because the real ones will get to the end of the post even knowing there won't be toy surprise. Just because it's good to be alive together. Boring each other to death. We can suck as bad as we need to, to get through this bullshit, and maybe one day we'll play Christmas Carols together, or murmur along with Ava Maria at the funeral mass, or pick up the bass in the nursing home Nation of Ulysses cover band. It's good to talk about love in an age of fear and death.

RIP Éliane Radigue

Conically Yours

I just did a podcast staring right at the camera and I see myself on screen and my jaw is wider than my forehead again. That's how I can tell I'm not taking care of myself. Before the endless winter apocalypse began I was getting in such good shape, doing these steady 30 mile bike rides punctuated by ferry stops. I haven't gained much weight but I'm a blob. Anyway, my head is more or less a cube. When it becomes conic with pointy end down I'm losing weight. Conic with pointy end up and I'm gaining weight. Just noting it in this long, long sigh. But also because my old weight loss blog is here—out of order and badly indexed—and I want to keep all the pieces connected. Also I feel judged right now with all the attention online and it's nice to own my own fatness instead of letting others own it for me.

Alt Text: A mass-produced knit cap in extremely bright blue, yellow, white, and red stripes, with a large blue, yellow, and red pom-pom on top. The forehead-covering part of the cap reads, in enormous white knit-pixelated letters, OLD BAY.

Gideon Lewis-Kraus: How Anthropic Sees Claude

Public opinion on LLMs like Claude varies widely—but how do the people who actually work at Anthropic think about it? On this week’s podcast, Paul and Rich are joined in the studio by New Yorker staff writer Gideon Lewis-Kraus to discuss his recent feature, which he reported from within Anthropic HQ. They discuss the piece, and then they hash out the real questions: What’s the correct literary metaphor for an LLM? Does an AI company really need psychologists for its chatbots? And, perhaps most importantly, should you be polite to Claude?

Public opinion on LLMs like Claude varies widely—but how do the people who actually work at Anthropic think about it? On this week’s podcast, Paul and Rich are joined in the studio by New Yorker staff writer Gideon Lewis-Kraus to discuss his recent feature, which he reported from within Anthropic HQ. They discuss the piece, and then they hash out the real questions: What’s the correct literary metaphor for an LLM? Does an AI company really need psychologists for its chatbots? And, perhaps most importantly, should you be polite to Claude?

Alt Text: Subject line/previews of emails from NYC public schools in Russian, French, and Bengali. Обратите внимание: школы будут закрыты без дистанционного обучения в понедельник, 23.02.2026. Проверьте schools.nyc.gov для получения последней информации о планах по открытию школ. Veuillez noter que les écoles seront fermées sans enseignement à distance le lundi 23 février 2026. Allez sur schools.nyc.gov pour obtenir les dernières informations sur les plans de réouverture des écoles. অনুগ্রহ করে লক্ষ্য করবেন: সোমবার, 02/23/2026 তারিখ, রিমোট শিক্ষা-নির্দেশনায় অংশগ্রহণ ছাড়াই স্কুলগুলো বন্ধ থাকবে। স্কুল পুনরায় খোলার পরিকল্পনা সংক্রান্ত সর্বসাম্প্রতিক তথ্যের জন্য schools.nyc.gov দেখুন।

Leading thoughts

I recently wrote for the big paper and it was with deep inner reluctance. I wish I could decide whether to be in the world or pull back from the world. The paper asked me to explain vibe coding, and I did so, because I think something big is coming there, and I'm deep in, and I worry that normal people are not able to see it and I want them to be prepared. But people can't just read something and hate you quietly; they can't see that you have provided them with a utility or a warning; they need their screech. You are distributed to millions of people, and become the local proxy for the emotions of maybe dozens of people, who disagree and demand your attention, and because you are the one in the paper you need to welcome them with a pastor's smile and deep empathy, and if you speak a word in your own defense they'll screech even louder. Most people are of course very nice. But I once went to a small local museum upstate, 30 years ago—the kind of old house museum where they assemble farm equipment and various landscape paintings and regional artifacts of manufacturing. It's a place for schoolchildren to touch a tractor. The somewhat leering fellow who ran it, overjoyed to have four college students out to see the world, ended the tour by taking us out back to the pond, where an inner tube was floating, tied to a short dock. He threw moldy and very large flatbreads into the ring of the tube, so large they touched its edges, and suddenly what appeared to be a thousand iridescently slimy eel-like fish swarmed up to it and ate the bread, so viciously en masse that some were thrown on top of the bread and began to asphyxiate, and could not get back down into the water, until the bread was eaten enough, and finally the whole living, seething, wetly slapping cluster of flesh sank out of view back into the pond. I will never forget that unbearable minute. We were shocked. He looked at us and said, “They're hungry.” And then we went back in and looked at some old shovels. That's how I feel about writing for a general audience in the age of social media.

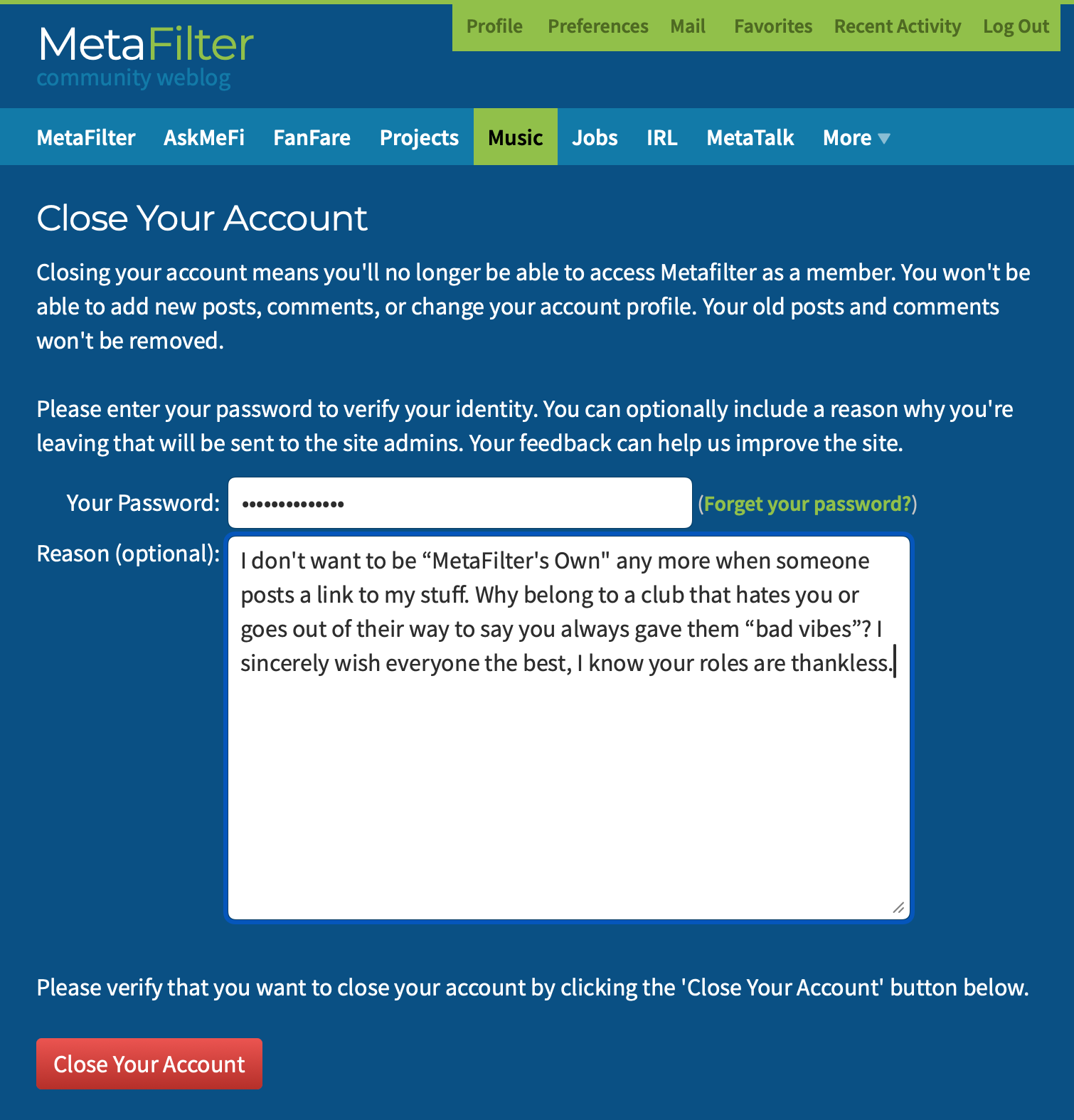

Someone on MetaFilter posted my NYT OpEd, making a point of linking to the exact post you're reading as well, and pointing out I was “MeFi's Own.” I know I was in the paper and I have to eat it, but it really felt like a setup, given the audience they were posting for.

A lot of the responses in there are the sort of vague assumptive semi-personal stuff you expect, people going out of their way to say I suck, or that there's no way a personal website could cost $25,000 (wait until I show you the taxonomy manager), punctuated by multiple developers going, No, this happened to me too. All the little pursed lip upvotes. Of course everyone just ignored those developers. One person wrote, “I love it when someone I have always had bad vibes about (Paul Ford) proves me right. Saving that into my chamber of treasures.” MetaFilter: Saving that into my chamber of treasures.

I still like to check in a few times a week. I have a funny loyalty to that site, because it's old web, and the community around it was my early community. But they've all left, some dramatically. And for many years I've found it to be a very unkind place in general, even though its 2000AD-era bones were very gentle. I first internalized the meanness 15 years ago, after seeing a thread of responses to a personal essay I wrote about going through IVF with my wife. It was a time of genuine confusion in my life and there was this very profound moment where I felt brutally rejected and judged by a place I thought of as friendly. It was bully shit, and nothing else.

So I haven't posted since that happened, I don't think. Maybe a few times on Ask. Then I saw that the title of the post was “Ftrain has left the station” and realized I could just peace out, and then I won't be “own”ed there any more, or feel like I owe it anything.

They make closing your account easy, thank God. Good product work there. A 25-year-old database entry is deleted. Absolutely no one will notice. A little self-indulgent treat just for me. Nothing changes in the world in any way. But I had bad vibes too, just like that anonymous person did about me. Everyone wins.